https://epistolae.ctl.columbia.edu/letter/141.html

Letters of royal and illustrious ladies of Great Britain, from the commencement of the twelfth century to the close of the reign of Queen Mary, volume 1, edited by Mary Anne Everett Wood, H. Colburn, London, 1846

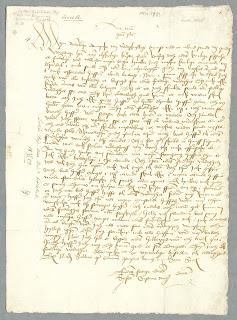

Above: Eleanor of Aquitaine.

Eleanor of Aquitaine (born 1122, died April 1, 1204) was queen consort of France from 1137 to 1152 and of England from 1154 to 1189, and duchess of Aquitaine in her own right from 1137 to 1204. As the heir of the House of Poitiers, rulers in southwestern France, she was one of the wealthiest and most powerful women in western Europe during the High Middle Ages. She was patron of literary figures such as Wace, Benoît de Sainte-Maure, and Bernart de Ventadorn. She led armies several times in her life and was a leader of the Second Crusade.

As the duchess of Aquitaine, Eleanor was the most eligible bride in Europe. Three months after becoming duchess upon the death of her father, William X, she married King Louis VII of France, son of her guardian, King Louis VI. As queen of France, she participated in the unsuccessful Second Crusade. Soon afterwards, Eleanor sought an annulment of her marriage, but her request was rejected by Pope Eugene III. However, after the birth of her second daughter Alix, Louis agreed to an annulment, as 15 years of marriage had not produced a son. The marriage was annulled on 21 March 1152 on the grounds of consanguinity within the fourth degree. Their daughters were declared legitimate, custody was awarded to Louis, and Eleanor's lands were restored to her.

As soon as the annulment was granted, Eleanor became engaged to the Duke of Normandy, who became King Henry II of England in 1154. Henry was her third cousin and 11 years younger. The couple married on Whitsun, 18 May 1152, eight weeks after the annulment of Eleanor's first marriage, in Poitiers Cathedral. Over the next 13 years, she bore eight children: five sons, three of whom became kings; and three daughters. However, Henry and Eleanor eventually became estranged. Henry imprisoned her in 1173 for supporting their son Henry's revolt against him. She was not released until 6 July 1189, when her husband Henry died and their third son, Richard the Lionheart, ascended the throne.

As queen dowager, Eleanor acted as regent while Richard went on the Third Crusade. Eleanor also lived well into the reign of Richard's heir and her youngest son, John.

Eleanor wrote this letter to Pope Celestine in around 1192, urging the liberation of her son Richard the Lionheart from the cruel captivity in which he was detained by the emperor Henry VI.

The letter:

Reverendo Patri, et domino Coelestino Dei gratia summo pontifici A. misera, et utinam miserabilis Anglorum regina, ducissa Normanniae, comitissa Andegaviae, miserae matri exhibere se misericordiae patrem.

Invidente locorum distantia prohibeor, beatissime papa, vobis praesentialiter loqui; necesse tamen est, ut plangam paululum dolorem meum. Et quis mihi tribuat ut scribantur sermones mei? Tota interius et exterius anxior: unde et verba mea dolore sunt plena. "Feris sunt timores, intus pugnae" (II Cor. VII); nec ad momentum mihi respirare liberum est "a tribulatione malorum et dolore" (Psal. CVI), "a tribulationibus, quae invenerunt nos nimis" (Psal. XLV) Tota dolore contabui, pellique meae consumptis carnibus adhaesit os meum (Psal. CI). "Defecerunt anni mei in gemitibus" (Psal. XXX), et utinam omnino deficiant. Utinam totus sanguis corporis mei jam emortui, cerebrum capitis, ossiumque medullae ita dissolvantur in lacrymas, ut in fletus tota pereffluam. Avulsa sunt a me viscera mea, baculum senectutis meae, "et lumen oculorum meorum" perdidi (Psal. XXXVII), meisque votis accederet, si Deus infelices oculos meos ne mala gentis meae ulterius videant, perpetua caecitate damnaret. "Quis det mihi ut pro te moriar, fili mi?" (II Reg. XVIII.) Matrem tantae miseriae respice misericordiae mater, aut si filius tuus fons misericordiae inexhaustus, peccata matris requirit a filio, ab ea quae sola deliquit, totum exigat, puniat impiam, et de poenis innocentis non rideat. "Qui coepit, ipse me conterat, tollat manum suam, et succidat me: et haec sit consolatio mea, ut affligens me dolore, non parcat" (Job VI).

Ego misera, et nulli miserabilis, cur in hujus detestandae senectutis ignominiam veni, duorum regnorum domina, duorumque regum mater exstiteram: avulsa sunt a me viscera mea; "generatio mea ablata est, et revoluta est a me" (Isa. XXXVIII). Rex junior et comes Britanniae in pulvere dormiunt, et eorum mater infelicissima vivere cogitur, ut irremediabiliter de mortuorum memoria torqueatur. Duo filii mihi supererant ad solatium, qui hodie mihi miserae et damnatae supersunt ad supplicium. Rex Ricardus tenetur in vinculis. Joannes frater ipsius regnum captivi depopulatur ferro, et vastat incendiis. "In omnibus versus est mihi Dominus in crudelem, et adversatur mihi in duritia manus suae" (Job XXX). Vere pugnat ira ejus contra me; ideo et filii mei pugnant inter se; si tamen pugna est, ubi unus vinculis arctatus affligitur; alius addens dolorem super dolorem ipsius crudeli tyrannide sibi regnum exsulis usurpare molitur. Bone Jesu, quis mihi tribuat, ut in inferno protegas me, et abscondas me, donec pertranseat furor tuus (Isa. XXVI), donec cessent sagittae, quae in me sunt, quarum indignatione spiritus meus totus ebibitur. Mors in voto mihi est, et vita in taedio, et cum sic moriar incessanter, in desideriis tamen habeo mori plenius; vivere compellor invita, ut vita mihi sit pabulum mortis et materia cruciatus. O felices, qui inexperti ludibria vitae hujus, et inopinatos eventus conditionis incertae beato praevenerunt aborsu! Quid facio? cur subsisto? quare moror misera, et non vado ut videam "quem diligit anima mea" (Cant. III), "vinctum in mendicitate et ferro?" (Psal. CVI.) utquid enim tanto tempore mater potuit oblivisci filii uteri sui? Tigrides erga fetus suos, et lamias etiam saeviores emollit affectio. Fluctuo tamen in dubio. Si enim abiero, deserens filii mei regnum, quod undique gravi hostilitate vastatur, erit in absentia mea omni consilio et solatio destitutum. Si autem substitero, desideratissimam mihi faciem filii mei non videbo. Non erit, qui liberationem filii mei studiose procuret, et, quod magis vereor, ad impossibilem pecuniae quantitatem delicatissimus adolescens tormentis urgebitur, tantaeque afflictionis impatiens facile in mortem suppliciis adigetur. O impie, crudelis et dire tyranne, qui non es veritus manus sacrilegas immittere in christum Domini, nec te regalis unctio, nec sanctae viae reverentia, nec Dei timor a tanta inhumanitate cohibuit! Porro princeps apostolorum adhuc in apostolica sede regnat et imperat, et in medio constitutus est judiciarius rigor; illudque restat, ut exeratis in maleficos, Pater, gladium Petri, quem ad hoc constituit super gentes et regna. Christi crux antecessit Caesaris aquilas, gladius Petri gladio Constantini, et apostolica sedes praejudicat imperatoriae potestati. Vestra potestas a Deo est, an ab hominibus? Nonne Deus deorum locutus est vobis in Petro apostolo dicens: "Quodcunque ligaveris super terram, erit ligatum et in coelis; et quodcunque solveris super terram, erit solutum et in coelis?" (Matth. XVI.) Quare ergo tanto tempore tam negligenter, imo tam crudeliter filium meum solvere differtis, aut potius non audetis? Sed dicetis hanc potestatem vobis in animabus, non in corporibus fuisse commissam. Esto: certe sufficit nobis, si eorum ligaveritis animas, qui filium meum ligatum in carcere tenent; filium meum solvere, vobis in expedito est, dummodo humanum timorem Dei timor evacuet.

Redde igitur mihi filium meum, vir Dei, si tamen vir Dei es, et non potius vir sanguinum, si in filii mei liberatione torpeas, ut sanguinem ejus de manu tua requirat Altissimus (Gen. IX). Heu, heu, si summus pastor in mercenarium pervertatur, si a facie lupi fugiat, si commissam sibi oviculam imo arietem electum, ducem Dominici gregis, in faucibus cruentae bestiae derelinquat! Bonus pastor alios pastores instruit, et informat, non ut fugiant, si viderint lupum venientem, sed animas suas pro ovibus suis ponant (Joan. X). Anima tua tibi, quaeso, salva sit, dummodo non dicam ovis tuae sed filii tui liberationem crebris legationibus, salutaribus monitis, comminationum tonitruis, generalibus interdictis, sententiis terribilibus studeas procurare. Sane vero vestram pro eo animam poneretis, qui pro eodem adhuc unum verbum dicere, aut scribere noluistis. Dei Filius, testimonio prophetae, de coelo descendit, ut educeret vinctos de lacu, in quo non erat aqua. Nunquid quod decuit Deum, dedecet Dei servum? Filius meus torquetur in vinculis, nec ad eum descendis, nec mittis, nec moveris super contritione Joseph. Christus hoc videt, et silet; sed opus Dei negligenter agentibus abundanter in summa districtione retribuet (Jer. XLVIII). Legati nobis jam tertio promissi sunt, nec sunt missi: utque verum fatear, ligati potius quam legati. Si filius meus in prosperis ageret, ad simplicem ejus vocationem festinantius accessissent, quia de magnifica ejus munificentia, et de publico regni quaestu suae legationis uberes manipulos exspectarent. Et quis quaestus eis gloriosior esse posset, quam regem liberare captivum, reddere pacem populis, religiosis quietem, et gaudium universis? Nunc autem "filii Ephrem intendentes et mittentes arcum in die belli conversi sunt" (Psal. LXXVII), et in tempore angustiae, dum lupus praedae incubat, canes muti latrare aut non possunt, aut nolunt. Haeccine promissio illa est, quam nobis apud castrum Radulphi cum tanta dilectionis et fidei protestatione fecistis? Quid profuit vobis simplicibus dare verba, et illudere vota innocentium inani fiducia? Sic olim rex Achab foedus amicitiae contraxisse cum Benadab perhibetur, illorumque mutuam dilectionem eventus habuisse infaustos audivimus; pugnas Judae, Joannis, Simonis Machabaeorum fratrum coelestis dispensatio felicibus prosperabat auspiciis; missa vero legatione sibi firmantes amicitiam Romanorum, Dei perdiderunt auxilium, nec eis semel, sed saepius venalis eorum familiaritas versa est in singultum. Solus desperare me cogitis, qui solus post Deum spes mea, populique nostri fiducia fueratis. "Maledictus qui confidit in homine" (Jer. XVII). Ubi est ergo nunc praestolatio mea? tu es, Domine, Deus meus. Ad te, Domine, qui laborem consideras, sunt oculi ancillae tuae. "Tu rex regum et Dominus dominantium" (I Tim. VI), "respice in faciem Christi tui" (Psal. LXXXIII), "da imperium puero tuo, et salvum fac filium ancillae tuae" (Psal. LXXXV), nec in eo punias delicta sui patris, aut malitiam matris suae. Ex certa et publica relatione cognovimus, quod imperator post Legiensis episcopi mortem, quem funesto gladio, longa tamen manu dicitur occidisse, Ostunensem episcopum, et quatuor episcopos comprovinciales ejus, Salernitanum etiam et Tranensem archiepiscopos coarctat miseria carcerali, et quod auctoritas apostolica nullatenus dissimulare debuerat, Siciliam, quam a temporibus Constantini constat esse patrimonium S. Petri, post legationes, post supplicationes, post comminationes apostolicae sedis, in perpetuum Romanae Ecclesiae praejudicium, usurpatione tyrannica occupavit. In omnibus his non est aversus furor ejus, sed adhuc manus ejus extenta. Gravia quidem intulit, sed certissime potestis exspectare in proximo graviora. Hi enim, qui debuerant esse columnae Ecclesiae, in omnes ventos arundinea levitate moventur. Utinam recolerent quod, propter negligentiam Heli sacerdotis ministrantis in Silo, gloria Domini de Israel translata est (I Reg. I); nec jam parabola temporis praeteriti est, sed praesentis; "quia repulit Dominus tabernaculum Silo, tabernaculum suum, ubi habitavit in hominibus, et tradidit in captivitatem virtutem eorum, et pulchritudinem eorum in manus inimici!" (Psal. LXXVII.) Imputatur eorum pusillanimitati, quod Ecclesia conculcatur, periclitatur fides, opprimitur libertas, dolus, patientia et iniquitas impunitate nutritur. Ubi est, quod Dominus Ecclesiae suae quandoque promisit: "Suges lac gentium, et mamilla regum lactaberis; ponam te in superbiam saeculorum, gaudium in generationem et generationem?" (Isa. LX.) Ecclesia olim superborum et sublimium colla propria virtute calcabat, legesque imperatorum sacros canones sequebantur. Nunc autem ordine turbato, non dicam canones, sed canonum conditores pravis legibus, et consuetudinibus exsecrandis arctantur. Detestanda potentum flagitia tolerantur; nec est, qui mutire audeat et in pauperum peccata duntaxat rigor canonicus exercetur. Ideo non immerito Anacharsis philosophus telis aranearum leges et canones comparabat, quae animalia debiliora retinent, fortia autem transmittunt. "Astiterunt reges terrae et principes convenerunt in unum adversus Christum Domini" (Psal. II), filium meum. Unus eum torquet in vinculis; alter terras illius crudeli hostilitate devastat. Et, ut verbo vulgari utar, "unus tondet, alter expilat; unus pedem tenet, alter excoriat." Haec videt summus pontifex, et gladium Petri supprimit in vagina repositum. Sic addit cornua peccatori, ipsaque taciturnitas ejus praesumitur ad consensum. Videtur enim consentire, qui cum possit et deberet non corripit, et dissimulatrix patientia societatis occultae scrupulo non carebit. Imminet, sicut praedixit apostolus, tempus dissensionis, ut perditionis filius reveletur, instantque tempora periculosa (II Tim. III), ut scindatur tunica Christi inconsutilis, ut rumpatur rete Petri, et catholicae unitatis soliditas dissolvatur. Initia malorum sunt haec (Matth. VIII): sentimus gravia, graviora timemus. Nec prophetissa, nec filia sum prophetae; plura tamen de futuris turbationibus dolor dicere suggerebat: sed ipsa verba, quae suggerit, subripit. Spiritum enim singultus intercipit, et animae vires moeror absorbens vocales meatus anxietate praecludit. Vale.

English translation (from source 2):

To the reverend father and lord Celestine, by God's grace highest pontiff, Eleanora the miserable, and I would I could add the commiserated, queen of England, duchess of Normandy, countess of Anjou, entreating him to shew himself a father of mercy to a miserable mother.

I am prevented, O holiest pope, by the great distance which parts us, from addressing you personally; yet I must bewail my grief a little, and who shall assist me to write my words?

I am all anxiety, internally and externally, whence my very words are full of grief. Without are fears, within contentions; nor have I a moment wherein to breathe freely from the tribulation of evils, and the grief occasioned by the troubles which ever find me out. I am all defiled with grief, and my bones cleave to my skin, for my flesh is wasted away. My years pass away in groanings, and I would they were altogether passed away. O that the whole blood of my body would now die, that the brain of my head and the marrow of my bones were so dissolved into tears that I might melt away in weeping! My very bowels are torn away from me; I have lost the light of my eyes, the staff of my old age: and, would God accede to my wishes, he would condemn me to perpetual blindness, that my wretched eyes might no longer behold the woes of my people. Who will grant me the boon of dying for thee, my son? O mother of mercy! look upon a mother so wretched; or if thy Son, the inexhausted fount of mercy, is avenging the sins of the mother on the son, let him exact vengeance from her who has alone sinned: let him punish me, the wicked one, and not amuse himself with the punishment of an innocent person. Let him who hath begun the task, who now bruises me, take away his hand and slay me; and this shall be my consolation, that, afflicting me with grief, he spares me not. O wretched me, yet pitied by none! why have I, the mistress of two kingdoms, the mother of two kings, reached the ignominy of a detested old age?

My bowels are torn away, my very race is destroyed and passing away from me. The young king and the Earl of Bretagne sleep in the dust, and their most unhappy mother is compelled to live that she may be ever tortured with the memory of the dead. Two sons yet survived to my solace, who now survive only to distress me, a miserable and condemned creature: King Richard is detained in bonds, and John, his brother, depopulates the captive's kingdom with the sword, and lays it waste with fire. In all things the Lord is become cruel towards me, and opposes me with a heavy hand. Truly his anger fights against me, when my very sons fight against each other, — if, indeed, that can be called a fight in which one party languishes in bonds, and the other, adding grief to grief, tries by cruel tyranny to usurp the exile's kingdom to himself.

O good Jesus! who will grant me thy protection, and hide me in hell itself till thy fury passes away, and till thy arrows which are in me, by whose vehemence my very spirit is drunk up, shall cease? I long for death, I am weary of life; and though I thus die incessantly, I yet desire to die more fully; I am reluctantly compelled to live, that my life may be the food of death and a means of torture. O happy ye who pass away by a fortunate abortion, without experiencing the waywardness of this life and the unexpected events of an uncertain condition! What do I? why do I remain? why do I, wretched, delay? why do I not go, that I may see him whom my soul loves, bound in beggary and irons? as though, at such a time, a mother could forget the son of her womb! Affection to their young softens tigers, nay, even the fiercer sorceresses.

Yet I fluctuate in doubt: for, if I go away, deserting my son's kingdom, which is laid waste on all sides with fierce hostility, it will in my absence be destitute of all counsel and solace; again, if I stay, I shall not see the face of my son, that face which I so long for. There will be none who will study to procure the liberation of my son, and, what I fear still more, the most delicate youth a will be tormented for an impossible quantity of money, and, impatient of so much affliction, will easily be brought to the agonies of death. Oh, impious, cruel, and dreadful tyrant! who hast not feared to lay sacrilegious hands on the anointed of the Lord! nor has the royal unction, nor the reverence due to a holy life, nor the fear of God, restrained thee from such inhumanity!

Yet the prince of the apostles still rules and reigns in the apostolic seat, and his judicial rigour is set up as a means of resort: this one thing remains, that you, O father, draw against these evil-doers the sword of Peter, which for this purpose is set over people and kingdoms. The cross of Christ excels the eagles of Cæsar, the sword of Peter the sword of Constantine, and the apostolic seat is placed above the imperial power. Is your power of God or of men? Has not the God of gods spoken to you by the Apostle Peter, that "whatsoever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatsoever you loose on earth shall be loosed also in heaven?" Wherefore, then, do you so long negligently, nay, cruelly, delay to free my son, or rather do not dare to do it? You will, perhaps, say that this power is given to you over souls, not over bodies: be it so; it will certainly suffice me if you will bind their souls who hold my son bound in prison. It is your province to loose my son, unless the fear of God has given way to human fear. Restore my son to me, then, O man of God, if indeed thou art a man of God and not a man of blood; for know that, if thou art sluggish in the liberation of my son, from thy hand will the Most High require his blood. Alas, alas for us, when the chief shepherd has become a mercenary, when he flies from the face of the wolf, when he leaves the little sheep committed to him, or rather the elect ram, the leader of the Lord's flock, in the jaws of the bloody beast of prey! The good Shepherd instructs and informs other shepherds not to fly when they see the wolf coming, but to lay down their lives for the sheep. Save, therefore, I entreat thee, thine own soul, whilst, by urgent embassies, by salutary advice, by the thunders of excommunication, by general interdicts, by terrible sentences, thou endeavourest to procure the liberation, I will not say of thy sheep merely, but of thy son. Though late, you ought to give your life for him, for whom, as yet, you have refused to write or speak a single word. The Son of God, as testifies the prophet, came down from heaven that he might bring up them that were bound from the pit in which was no water. Now, would not that which was fitting for God to do become the servant of God? My son is tormented in bonds, yet you go not down to him, nor send, nor are moved by the sorrow of Joseph. Christ sees this and is silent; yet at the last there shall be fearful retribution for those who do the work of God negligently. Ambassadors have been promised to us three times, but never sent; so that, to speak the truth, they are bound rather than sent. If my son were in prosperity, they would eagerly hasten at his lightest call, because they would expect rich handfuls for their embassy from his great munificence and the public profit of the kingdom. But what profit could be more glorious to them than to liberate a captive king, to restore peace to the people, quiet to the religious, and joy to all? Now, truly, the sons of Ephraim, who bent and sent forth the bow, have turned round in the day of battle; and in the time of dis tress, when the wolf comes upon the prey, they are dumb dogs who either cannot or will not bark. Is this the promise you made me at the castle of Ralph with such protestations of favour and good faith? What availed it to give words only to my simplicity, and to illude by a fond trust the wishes of the innocent? So, in olden time, was King Ahab forbidden to make alliance with Benhadad, and we have heard the fatal issue of their mutual love. A heavenly providence prospered the wars of Judas, John, and Simon, the Maccabæan brothers, under happy auspices; but when they sent an embassy to secure the friendship of the Romans, they lost the help of God, and, not once alone, but often was their venal intimacy cause of bitter regret. You alone, who were my hope after God, and the trust of my people, force me to despair. Cursed be he who trusteth in man. Where is now my refuge? Thou, O Lord, my God. To thee, O Lord, who considerest my distress, are the eyes of thine handmaid lifted up. Thou, O King of kings and Lord of lords, look upon the face of thine Anointed, give empire to thy Son, and save the son of thine handmaid, nor visit upon him the crimes of his father or the wickedness of his mother!

We know by certain and public relation that the emperor, after the death of the Bishop of Liege (whom he is said to have slain with a fatal sword, though wielded by a remote hand), miserably imprisoned the Bishop of Ostia and four other provincials, the Bishop of Salerno, and the Archbishop of Treves; and the apostolic authority cannot deny that, to the perpetual prejudice of the Roman church, he has, in spite of embassies, supplications, and threats of the apostolic seat, taken possession of Sicily, which from the times of Constantine has been the patrimony of St. Peter. Yet with all this his fury is not yet turned away, but yet is his hand stretched forth. Fearful things he has already done, but worse are still certainly to be expected; for those who ought to be the pillars of the church are swayed with reed-like lightness by every wind. Oh, would they but remember that it was through the negligence of Eli, the priest ministering in Shiloh, that the glory of the Lord passed away from Israel! Nor is that a mere parable of the past, but of the present. For the Lord drove from Shiloh the tabernacle, his tabernacle, where he had dwelt amongst men, and gave their strength into captivity and their beauty into the hands of the enemy.

It is imputed to your pusillanimity that the church is trampled upon, the faith perilled, liberty oppressed, deceit encouraged by patience, iniquity by impunity. Where is the promise of God when he said to his church, "Thou shalt suck the milk of the Gentiles, and shalt suck the breasts of kings?" "I will make thee the pride of ages, and a joy from generation to generation." Once the church, by its own strength, trod upon the necks of the proud and the lofty, and the laws of emperors obeyed the sacred canons. But things are changed, and not only the canons, but the very formers of the canons, are restrained by base laws and execrable customs. The detestable crimes of the powerful are borne with. None dare murmur, and canonical rigour falls on the sins of the poor alone. Therefore, not without reason did Anacharsis the philosopher compare laws and canons to spiders' webs, which retain weaker animals but let the stronger go." The kings of the earth have set themselves, and the rulers have taken counsel together," against my son, the anointed of the Lord. One binds him in chains, another devastates his lands with cruel hostility, or, to use a vulgar phrase, "One clips and another plunders; one holds the foot and another skins it." The highest pontiff sees these things, and yet bids the sword of Peter slumber in its scabbard; so he adds boldness to the sinner, his silence being presumed to indicate consent. He who corrects a not when he can and ought seems even to consent, and his dissimulating patience shall not want the scruple of hidden companionship. The time of dissension predicted by the apostle draws on, when the son of perdition shall be revealed; dangerous times are at hand, when the seamless garment of Christ is cut, the net of Peter is broken, and the solidity of Catholic unity dissolved. These are the beginnings of sorrows. We feel bad things; we fear worse. I am no prophetess, nor the daughter of a prophet, but grief has suggested many things about future disturbances; yet it steals away the very words which it suggests. A sob intercepts my breath, and absorbing grief shuts up by its anxieties the vocal passages of my soul. Farewell.