http://nosauvelta.blogspot.com/2013/02/because-love-could-not-stop-for-death.html#axzz6WNebcFBY

My 100th post on this blog!

My 100th post on this blog!

This letter was found in 1998 in the tomb of 30 year old Eung-Tae Lee, a member of the Goseong Yi clan who died suddenly in 1586, leaving behind a devastated — and pregnant — wife. They had even already decided on a name for the baby, as the letter is addressed to "Won's father". The young widow's name has been lost to history, but because of her great devotion to her husband, I will call her Sarang, which means "love" in Korean. She would surely appreciate that. They lived in or near what is now Andong in the Gyeongsangbuk-do Province of South Korea during the era of the Joseon dynasty.

While Eung-Tae struggled through his illness, Sarang made a pair of traditional mituri sandals as a get-well present for him, sewn from hemp fabric and strands of her own hair; and she never stopped hoping even when the end was obvious and inevitable. When he died, Sarang was horrified at the very idea of him never being able to wear his new mituri, so she had them placed with him in his tomb, wanting him to have them anyway.

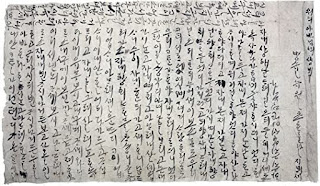

Before the burial, Sarang poured her heart out to her late husband in this letter, written on June 1 in 1586, which is one of the Years of the Fire Dog (Byeongsul) in the sexagenary cycle. Sarang was angry at Eung-Tae for having left her alone with a baby waiting for him when they were at the height of marital bliss, and she was confused at how he could have died so suddenly and so soon. She was desperately lonely and anxious for herself and the baby, and she reminded her husband about how he promised that they would grow old together. Eung-Tae considered himself and Sarang to be very fortunate and so happy compared to other couples because they were so deeply in love. She wanted to die, just to be able to see him again and stay with him forever. She begged him to read the letter in the afterlife and to visit her in her dreams. One can only imagine what a state Sarang must have been in at the funeral. Did she watch silently as Eung-Tae and his many belongings were placed into the tomb? Although it would not have been considered proper, did she weep openly or shout, did she faint and have to be held up by a friend or relative? We will never know.

The letter was placed in the tomb with Eung-Tae, whose body was found when the city of Andong began moving a centuries-old cemetery to make way for new houses. Because he died at a young age, his death was left unrecorded, as was the custom of the time; and so his grave was eventually left unclaimed while the people around him had descendants to claim them. Sarang's letter to him is one of the oldest examples of Korean writing using the Hangul script. Hangul had been introduced in 1446, and at the time, its original form was called Hunminjeongeum. The letter is written top to bottom, right to left, and when Sarang ran out of space, she had to turn it counterclockwise, as paper was such an expensive commodity in those days. She used no spacing at all and different letters were present. Sarang used the archaic informal second-person pronoun "janae", which is a huge discovery for historical linguistics and the study of Middle Korean since it was known to be used by husbands to their wives, but until the letter's discovery, there were no known examples of wives using the pronoun in addressing their husbands.

This letter, the mituri, and the tiny notes on them are the only remnants of Sarang's life. Her devoted love for her beloved Eung-Tae has inspired two novels, a documentary film, and an opera. The letter is very popular among today's Koreans and Japanese tourists, and a statue of Sarang stands at the grave site.

The letter:

원이 아바님께 샹백

병슐 뉴월 초하룻날 지븨셔

자네 샹해 날다려 닐오듸 둘히 머리 셰도

록 사다가 함께 죽쟈 하시더니 엇디하

야 나랄 두고 자내 몬져 가시난 날하고

자식하며 뉘게 걸하야 엇디하야 살라

하야 다 더디고 자내 몬져 가시난고 자내

날 향회 마아믈 엇디 가지며 난 자내 향

회 마으믈 엇디 가지던고 믜양 자내 다려 내닐오듸

한듸 누어셔 이보소 남도 우리

가티 서로 에엿삐 녀겨 사랑하리 남도

우리 가탄가 하야 자내다려 니라더니 엇디

그런 이를 생각디 아녀 나랄 바리고 몬져

갓난고 자내 여회고 아마려 내 살셰 업사니

수이 자내한듸 가고져하니 날 다려가소

자내 향회 마아믈 차생 니즐준리

없사니 아마래 션운 뜨디 가이없사니

이내 안한 어듸다가 두고 자식다리고

자내를 그려 살려뇨 하노이다

이내 유무 보시고 내 꾸메 자셰와 니라소

내꾸메 이 보신 말 자셰 듣고져 하야

이리 서년뇌 자세보시고 날 다려 니로소

자내 내 밴 자식 나거든 보고 사를 일란고

그리 가시듸 밴자식 나거든 누를

아빠 하라 하시난고 아마려 한들

내 안 가틀가 이런 텬디 가슨 한이리

하늘 아래 또 이실가 자내난 한갓 그리 가 겨실 뿌거니와 아마려 한들 내 안가티

셜운가 그지 그지 가이없서 다 몬서 대강만 뎍뇌 이 유무 자세 보시고

내 꾸메 자셰와 븨고 자셰 니라소 나난 꾸믄 자내 보려 믿고 인뇌이다 몰래 뵈쇼셔

하 그지그지 업서 이만 젹뇌이다

원이 아바님께 샹백

병슐 뉴월 초하룻날 지븨셔

자네 샹해 날다려 닐오듸 둘히 머리 셰도

록 사다가 함께 죽쟈 하시더니 엇디하

야 나랄 두고 자내 몬져 가시난 날하고

자식하며 뉘게 걸하야 엇디하야 살라

하야 다 더디고 자내 몬져 가시난고 자내

날 향회 마아믈 엇디 가지며 난 자내 향

회 마으믈 엇디 가지던고 믜양 자내 다려 내닐오듸

한듸 누어셔 이보소 남도 우리

가티 서로 에엿삐 녀겨 사랑하리 남도

우리 가탄가 하야 자내다려 니라더니 엇디

그런 이를 생각디 아녀 나랄 바리고 몬져

갓난고 자내 여회고 아마려 내 살셰 업사니

수이 자내한듸 가고져하니 날 다려가소

자내 향회 마아믈 차생 니즐준리

없사니 아마래 션운 뜨디 가이없사니

이내 안한 어듸다가 두고 자식다리고

자내를 그려 살려뇨 하노이다

이내 유무 보시고 내 꾸메 자셰와 니라소

내꾸메 이 보신 말 자셰 듣고져 하야

이리 서년뇌 자세보시고 날 다려 니로소

자내 내 밴 자식 나거든 보고 사를 일란고

그리 가시듸 밴자식 나거든 누를

아빠 하라 하시난고 아마려 한들

내 안 가틀가 이런 텬디 가슨 한이리

하늘 아래 또 이실가 자내난 한갓 그리 가 겨실 뿌거니와 아마려 한들 내 안가티

셜운가 그지 그지 가이없서 다 몬서 대강만 뎍뇌 이 유무 자세 보시고

내 꾸메 자셰와 븨고 자셰 니라소 나난 꾸믄 자내 보려 믿고 인뇌이다 몰래 뵈쇼셔

하 그지그지 업서 이만 젹뇌이다

Romanisation:

won-i abanimkke syangbaeg

byeongsyul nyuwol chohalusnal jibuisyeo

jane syanghae naldalyeo nil-odui dulhi meoli syedo

log sadaga hamkke jugjya hasideoni eosdiha

ya nalal dugo janae monjyeo gasinan nalhago

jasighamyeo nwige geolhaya eosdihaya salla

haya da deodigo janae monjyeo gasinango janae

nal hyanghoe maameul eosdi gajimyeo nan janae hyang

hoe ma-eumeul eosdi gajideongo muiyang janae dalyeo naenil-odui

handui nueosyeo iboso namdo uli

gati seolo eyeosppi nyeogyeo salanghali namdo

uli gatanga haya janaedalyeo niladeoni eosdi

geuleon ileul saeng-gagdi anyeo nalal baligo monjyeo

gasnango janae yeohoego amalyeo nae salsye eobsani

su-i janaehandui gagojyeohani nal dalyeogaso

janae hyanghoe maameul chasaeng nijeuljunli

eobs-sani amalae syeon-un tteudi gaieobs-sani

inae anhan eoduidaga dugo jasigdaligo

janaeleul geulyeo sallyeonyo hanoida

inae yumu bosigo nae kkume jasyewa nilaso

naekkume i bosin mal jasye deudgojyeo haya

ili seonyeonnoe jasebosigo nal dalyeo niloso

janae nae baen jasig nageodeun bogo saleul illango

geuli gasidui baenjasig nageodeun nuleul

appa hala hasinango amalyeo handeul

nae an gateulga ileon tyeondi gaseun han-ili

log sadaga hamkke jugjya hasideoni eosdiha

ya nalal dugo janae monjyeo gasinan nalhago

jasighamyeo nwige geolhaya eosdihaya salla

haya da deodigo janae monjyeo gasinango janae

nal hyanghoe maameul eosdi gajimyeo nan janae hyang

hoe ma-eumeul eosdi gajideongo muiyang janae dalyeo naenil-odui

handui nueosyeo iboso namdo uli

gati seolo eyeosppi nyeogyeo salanghali namdo

uli gatanga haya janaedalyeo niladeoni eosdi

geuleon ileul saeng-gagdi anyeo nalal baligo monjyeo

gasnango janae yeohoego amalyeo nae salsye eobsani

su-i janaehandui gagojyeohani nal dalyeogaso

janae hyanghoe maameul chasaeng nijeuljunli

eobs-sani amalae syeon-un tteudi gaieobs-sani

inae anhan eoduidaga dugo jasigdaligo

janaeleul geulyeo sallyeonyo hanoida

inae yumu bosigo nae kkume jasyewa nilaso

naekkume i bosin mal jasye deudgojyeo haya

ili seonyeonnoe jasebosigo nal dalyeo niloso

janae nae baen jasig nageodeun bogo saleul illango

geuli gasidui baenjasig nageodeun nuleul

appa hala hasinango amalyeo handeul

nae an gateulga ileon tyeondi gaseun han-ili

haneul alae tto isilga janaenan hangas geuli ga gyeosil ppugeoniwa amalyeo handeul nae angati

syeol-unga geuji geuji gaieobs-seo da monseo daegangman dyeognoe i yumu jase bosigo

nae kkume jasyewa buigo jasye nilaso. Nanan kkumeun janae bolyeo midgo innoeida. Mollae boesyosyeo.

syeol-unga geuji geuji gaieobs-seo da monseo daegangman dyeognoe i yumu jase bosigo

nae kkume jasyewa buigo jasye nilaso. Nanan kkumeun janae bolyeo midgo innoeida. Mollae boesyosyeo.

Ha geujigeuji eobseo iman jyeognoeida.

Modern Korean translation:

원이 아버님께 올림--병술년 유월 초하룻날, 집에서

당신 언제나 나에게 ‘둘이 머리 희어지도록 살다가 함께 죽자’고 하셨지요. 그런데 어찌 나를 두고 당신 먼저 가십니까. 나와 어린 아이는 누구의 말을 듣고 어떻게 살라고 다 버리고 당신 먼저 가십니까. 당신 나에게 마음을 어떻게 가져 왔고 또 나는 당신에게 마음을 어떻게 가져 왔었나요. 함께 누우면 언제나 나는 당신에게 말하곤 했지요. ‘여보, 다른 사람들도 우리처럼 서로 어여삐 여기고 사랑할까요.’ ‘남들도 정말 우리 같을까요.’ 어찌 그런 일들 생각하지도 않고 나를 버리고 먼저 가시는가요. 당신을 여의고는 아무리 해도 나는 살 수 없어요. 빨리 당신께 가고 싶어요. 나를 데려가 주세요. 당신을 향한 마음을 이승에서 잊을 수가 없고 서러운 뜻 한이 없습니다. 내 마음 어디에 두고 자식 데리고 당신을 그리워하며 살 수 있을까 생각합니다. 이 내 편지 보시고 내 꿈에 와서 자세히 말해 주세요. 꿈속에서 당신 말을 자세히 듣고 싶어서 이렇게 써서 넣어드립니다. 자세히 보시고 나에게 말해 주세요. 당신 내 뱃속의 자식 낳으면 보고 말할 것 있다 하고 그렇게 가시니, 뱃속의 자식 낳으면 누구를 아버지라 하라시는 거지요. 아무리 한들 내 마음 같겠습니까. 이런 슬픈 일이 하늘 아래 또 있겠습니까. 당신은 한갓 그곳에 가 계실 뿐이지만 아무리 한들 내 마음같이 서럽겠습니까. 한도 없고 끝도 없어 다 못 쓰고 대강만 적습니다. 이 편지 자세히 보시고 내 꿈에 와서 당신 모습 자세히 보여 주시고 또 말해 주세요. 나는 꿈에는 당신을 볼 수 있다고 믿고 있습니다. 몰래 와서 보여주세요. 하고 싶은 말 끝이 없어 이만 적습니다.

원이 아버님께 올림--병술년 유월 초하룻날, 집에서

당신 언제나 나에게 ‘둘이 머리 희어지도록 살다가 함께 죽자’고 하셨지요. 그런데 어찌 나를 두고 당신 먼저 가십니까. 나와 어린 아이는 누구의 말을 듣고 어떻게 살라고 다 버리고 당신 먼저 가십니까. 당신 나에게 마음을 어떻게 가져 왔고 또 나는 당신에게 마음을 어떻게 가져 왔었나요. 함께 누우면 언제나 나는 당신에게 말하곤 했지요. ‘여보, 다른 사람들도 우리처럼 서로 어여삐 여기고 사랑할까요.’ ‘남들도 정말 우리 같을까요.’ 어찌 그런 일들 생각하지도 않고 나를 버리고 먼저 가시는가요. 당신을 여의고는 아무리 해도 나는 살 수 없어요. 빨리 당신께 가고 싶어요. 나를 데려가 주세요. 당신을 향한 마음을 이승에서 잊을 수가 없고 서러운 뜻 한이 없습니다. 내 마음 어디에 두고 자식 데리고 당신을 그리워하며 살 수 있을까 생각합니다. 이 내 편지 보시고 내 꿈에 와서 자세히 말해 주세요. 꿈속에서 당신 말을 자세히 듣고 싶어서 이렇게 써서 넣어드립니다. 자세히 보시고 나에게 말해 주세요. 당신 내 뱃속의 자식 낳으면 보고 말할 것 있다 하고 그렇게 가시니, 뱃속의 자식 낳으면 누구를 아버지라 하라시는 거지요. 아무리 한들 내 마음 같겠습니까. 이런 슬픈 일이 하늘 아래 또 있겠습니까. 당신은 한갓 그곳에 가 계실 뿐이지만 아무리 한들 내 마음같이 서럽겠습니까. 한도 없고 끝도 없어 다 못 쓰고 대강만 적습니다. 이 편지 자세히 보시고 내 꿈에 와서 당신 모습 자세히 보여 주시고 또 말해 주세요. 나는 꿈에는 당신을 볼 수 있다고 믿고 있습니다. 몰래 와서 보여주세요. 하고 싶은 말 끝이 없어 이만 적습니다.

Romanisation of the modernised version (from source 3):

Won-i abeonimkke ollim -- Byeongsulnyeon yuwol chohalusnal, jib-eseo

Dangsin eonjena na-ege "dul-i meoli huieojidolog saldaga hamkke jugja" go hasyeossjiyo. Geuleonde eojji naleul dugo dangsin meonjeo gasibnikka. Nawa eolin aineun nuguui mal-eul deudgo eotteohge sallago da beoligo dangsin meonjeo gasibnikka. Dangsin na-ege ma-eum-eul eotteohge gajyeo wassgo tto naneun dangsin-ege ma-eum-eul eotteohge gajyeo wass-eossnayo. Hamkke nuumyeon eonjena naneun dangsin-ege malhagon haessjiyo. "Yeobo, daleun salamdeuldo ulicheoleom seolo eoyeoppi yeogigo salanghalkkayo." "Namdeuldo jeongmal uli gat-eulkkayo." Eojji geuleon ildeul saeng-gaghajido anhgo naleul beoligo meonjeo gasineungayo. Dangsin-eul yeouigoneun amuli haedo naneun sal su eobs-eoyo. Ppalli dangsinkke gago sip-eoyo. Naleul delyeoga juseyo.dangsin-eul hyanghan ma-eum-eul iseung-eseo ij-eul suga eobsgo seoleoun tteus han-i eobs-seubnida. Nae ma-eum eodie dugo jasig deligo dangsin-eul geuliwohamyeo sal su iss-eulkka saeng-gaghabnida. I nae pyeonji bosigo nae kkum-e waseo jasehi malhae juseyo. Kkumsog-eseo dangsin mal-eul jasehi deudgo sip-eoseo ileohge sseoseo neoh-eodeulibnida. Jasehi bosigo na-ege malhae juseyo. Dangsin nae baes-sog-ui jasig nah-eumyeon bogo malhal geos issda hago geuleohge gasini, baes-sog-ui jasig nah-eumyeon nuguleul abeojila halasineun geojiyo. Amuli handeul nae ma-eum gatgessseubnikka. Ileon seulpeun il-i haneul alae tto issgessseubnikka. Dangsin-eun hangas geugos-e ga gyesil ppun-ijiman amuli handeul nae ma-eumgat-i seoleobgessseubnikka. Hando eobsgo kkeutdo eobs-eo da mos sseugo daegangman jeogseubnida. I pyeonji jasehi bosigo nae kkum-e waseo dangsin moseub jasehi boyeo jusigo tto malhae juseyo. Naneun kkum-eneun dangsin-eul bol su issdago midgo issseubnida. Mollae waseo boyeojuseyo. Hago sip-eun mal kkeut-i eobs-eo iman jeogseubnida.

Dangsin eonjena na-ege "dul-i meoli huieojidolog saldaga hamkke jugja" go hasyeossjiyo. Geuleonde eojji naleul dugo dangsin meonjeo gasibnikka. Nawa eolin aineun nuguui mal-eul deudgo eotteohge sallago da beoligo dangsin meonjeo gasibnikka. Dangsin na-ege ma-eum-eul eotteohge gajyeo wassgo tto naneun dangsin-ege ma-eum-eul eotteohge gajyeo wass-eossnayo. Hamkke nuumyeon eonjena naneun dangsin-ege malhagon haessjiyo. "Yeobo, daleun salamdeuldo ulicheoleom seolo eoyeoppi yeogigo salanghalkkayo." "Namdeuldo jeongmal uli gat-eulkkayo." Eojji geuleon ildeul saeng-gaghajido anhgo naleul beoligo meonjeo gasineungayo. Dangsin-eul yeouigoneun amuli haedo naneun sal su eobs-eoyo. Ppalli dangsinkke gago sip-eoyo. Naleul delyeoga juseyo.dangsin-eul hyanghan ma-eum-eul iseung-eseo ij-eul suga eobsgo seoleoun tteus han-i eobs-seubnida. Nae ma-eum eodie dugo jasig deligo dangsin-eul geuliwohamyeo sal su iss-eulkka saeng-gaghabnida. I nae pyeonji bosigo nae kkum-e waseo jasehi malhae juseyo. Kkumsog-eseo dangsin mal-eul jasehi deudgo sip-eoseo ileohge sseoseo neoh-eodeulibnida. Jasehi bosigo na-ege malhae juseyo. Dangsin nae baes-sog-ui jasig nah-eumyeon bogo malhal geos issda hago geuleohge gasini, baes-sog-ui jasig nah-eumyeon nuguleul abeojila halasineun geojiyo. Amuli handeul nae ma-eum gatgessseubnikka. Ileon seulpeun il-i haneul alae tto issgessseubnikka. Dangsin-eun hangas geugos-e ga gyesil ppun-ijiman amuli handeul nae ma-eumgat-i seoleobgessseubnikka. Hando eobsgo kkeutdo eobs-eo da mos sseugo daegangman jeogseubnida. I pyeonji jasehi bosigo nae kkum-e waseo dangsin moseub jasehi boyeo jusigo tto malhae juseyo. Naneun kkum-eneun dangsin-eul bol su issdago midgo issseubnida. Mollae waseo boyeojuseyo. Hago sip-eun mal kkeut-i eobs-eo iman jeogseubnida.

English translation:

To Won's Father

June 1, 1586

June 1, 1586

You always said, "Dear, let's live together until our hair turns gray and die on the same day." How could you pass away without me? Who should I and our little boy listen to and how should we live? How could you go ahead of me?

How did you bring your heart to me and how did I bring my heart to you? Whenever we lay down together you always told me, "Dear, do other people cherish and love each other like we do? Are they really like us?" How could you leave all that behind and go ahead of me?

I just cannot live without you. I just want to go to you. Please take me to where you are. My feelings toward you I cannot forget in this world and my sorrow knows no limit. Where would I put my heart in now and how can I live with the child missing you?

Please look at this letter and tell me in detail in my dreams. Because I want to listen to your saying in detail in my dreams I write this letter and put it in. Look closely and talk to me.

When I give birth to the child in me, who should it call father? Can anyone fathom how I feel? There is no tragedy like this under the sky.

You are just in another place, and not in such a deep grief as I am. There is no limit and end to my sorrows that I write roughly. Please look closely at this letter and come to me in my dreams and show yourself in detail and tell me. I believe I can see you in my dreams. Come to me secretly and show yourself. There is no limit to what I want to say and I stop here.