Source:

Letters of royal and illustrious ladies of Great Britain, from the commencement of the twelfth century to the close of the reign of Queen Mary, volume 1, edited by Mary Anne Everett Wood, H. Colburn, London, 1846

Above: Isabella of Angoulême, queen consort of England, in an 1875 lithograph by W. H. Mote after J. W. Wright.

Above: King Henry III of England.

Above: Princess Joan of England, who was nine or ten years old at the time this letter was written.

Isabella of Angoulême (born between circa 1186 and 1188, died June 4, 1246) was Queen of England as the second wife of King John from 1200 until John's death in 1216. She was also suo jure Countess of Angoulême from 1202 until 1246.

Isabella had five children by the king, including his heir, later Henry III. In 1220, Isabella married Hugh X of Lusignan, Count of La Marche, by whom she had another nine children.

Some of Isabella's contemporaries, as well as later writers, claim that Isabella formed a conspiracy against King Louis IX of France in 1241, after being publicly snubbed by his mother, Blanche of Castile, for whom she had a deep-seated hatred. In 1244, after the plot had failed, Isabella was accused of attempting to poison the king. To avoid arrest, she sought refuge in Fontevraud Abbey, where she died two years later, but none of this can be confirmed.

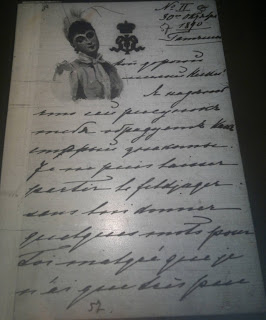

The letter:

Carissimo filio suo Henrico, Dei gratia regi Angliae, domino Hiberniae, duci Normanniae, Aquitaniae, comiti Andegaviae, Y[sabella] eadem gratia regina Angliae, dominae Hiberniae, ducissa Normanniae, Aquitaniae, comitissa Andegaviae et Engolismae, salutem et maternam benedictionem.

Significamus autem vobis quod cum comites Marchiae et Angolismae in fata decesserunt, dominus Hugo de Leziniaco quasi solus et sine herede in partibus Pictaviae remansit, et non permiserunt amici ejus quod filia nostra lege maritali ei copularetur, quae tam tenerae aetatis est; sed consilium ei dederunt quod talem duceret in uxorem de qua cito heres exiret, et prolocutum fuit quod uxorem caperet in Francia. Quod si hoc fuisset, tota terra vestra in Pictavia et Gasconia et nostra amitteretur. Nos autem videntes magnum periculum quod potuit emergere si istud maritagium foret, (et consiliarii vestri nullum consilium in nobis apponere voluerunt) dictum H[ugonem], comitem Marchiae, duximus in dominum; et sciat Deus quod nos magis hoc fecimus pro utilitate vestra quam pro nostra. Unde vos rogamus, ut carum filium, quod hoc vobis placeat, cum hoc cedat maxime utilitati vestrae et vestrorum, et precamur vos diligenter quod ei reddatis jus suum, scilicet Niortum, Castrum Exonense et de Rokingham, et tria millia et quingentas marcas quas pater vester, maritus quondam noster, nobis legavit: et ita, si placet, vos habeatis erga eum qui tam potens est, quod in vobis non remaneat quin vobis bene serviat. Nam bonum animum habet vobis fideliter servire pro toto posse suo, et certae sumus et in manu capimus quod bene vobis serviet, si vos ei jura sua reddideritis: et ideo consulimus quod super praedictis consilium opportunum habeatis. Et quando vobis placuerit, pro filia nostra, sorore vestra, mittatis, quoniam eam penes non habemus; et per certum nuncium et literas patentes et eam nobis mittetis.

English translation (from source 2):

To her dearest son Henry, by the grace of God king of England, lord of Ireland, duke of Normandy and Aquitaine, earl of Anjou, Isabella, by the same grace queen of England, lady of Ireland, duchess of Normandy and Aquitaine, countess of Anjou and Angoulême, sends health and her maternal benediction.

We hereby signify to you that when the Earls of March and Eu departed this life, the lord Hugh de Lusignan remained alone and without heirs in Poictou, and his friends would not permit that our daughter should be united to him in marriage, because her age is so tender, but counselled him to take a wife from whom he might speedily hope for an heir; and it was proposed that he should take a wife in France, which if he had done, all your land in Poictou and Gascony would be lost. We, therefore, seeing the great peril that might accrue if that marriage should take place, when our counsellors could give us no advice, ourselves married the said Hugh earl of March; and God knows that we did this rather for your benefit than our own. Wherefore we entreat you, as our dear son, that this thing may be pleasing to you, seeing it conduces greatly to the profit of you and yours; and we earnestly pray you that you will restore to him his lawful right, that is Niort, the castles of Exeter and Rockingham, and 3500 marks, which your father, our former husband, bequeathed to us; and so, if it please you, deal with him, who is so powerful, that he may not remain against you, since he can serve you well — for he is well-disposed to serve you faithfully with all his power; and we are certain and undertake that he shall serve you well if you will restore to him his rights, and, therefore, we advise that you take opportune counsel on these matters; and, when it shall please you, you may send for our daughter, your sister, by a trusty messenger and your letters patent, and we will send her to you.